Nannie Helen Burroughs: Leading Black Voice Advocating for Faith, Educating Girls, and Women’s Right to Vote

African American women stand above all other groups of men and women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds for their high religious observance levels. The 2007 U. S. Religious Landscape Survey reported, “More than eight-in-ten black women (84%) say religion is very important to them” and “six-in-ten (59%) …attend religious services at least once a week.”[1] From the early twentieth century to the late 1950s, Nannie Helen Burroughs winsomely and persuasively stood as a leading Black voice advocating for faith, educating girls, and women’s right to vote.

“Woman Arise”

Twenty-one-year-old Nannie Helen Burroughs titled her speech, “How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping.” She delivered it at the National Baptist Convention’s (NBC) 1900 annual meeting in Richmond, Virginia.[2] Burroughs passionately articulated her fellow Black women’s discontent and expressed their appeal to serve as co-workers alongside their Baptist brothers to evangelize the world for Christ. By the meeting’s conclusion, NBC approved the Woman’s Convention (WC) establishment and elected its first slate of national and state officers. With Burroughs named the corresponding secretary, they chose a motto, “The world for Christ. Woman arise. He calleth for thee.” A short three years later, approximately a million black Baptist women were part of the WC. The “Sisters” speech effectively launched Burroughs six-decades-long career as a nationally recognized religious leader.[3]

Family and Education

Born in Virginia in 1879 to former slaves, Burroughs understood from childhood the inherent life challenges for a “colored girl.” Her father, John Burroughs, was an itinerant preacher, and unfortunately, mostly absent. Her mother, Jennie Poindexter Burroughs, a Sunday school teacher, supported the family through domestic service work. Nannie also lived with her grandmother, whom she described as a “seamstress” and “philosopher.”[4]

Firmly believing the best future depended on a good education, Jennie moved the family to Washington, D.C., when Nannie was five years old. After completing her early grades, she enrolled in the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth (established in 1870 and later called M Street High School), the first US public high school for black students and “the nation’s preeminent public institution of black higher learning.” Before graduating with honors, she created a literary and debate club for fellow students called the Harriet Beecher Stowe Literary Society.[5]

Founder of the National Training School for Women and Girls

After suffering the disappointment of two job rejections, Burroughs was inspired with an idea which she attributed to God. She dreamed of establishing a private school to educate and develop young women into leaders. She wanted a school “that would give all sorts of girls a fair chance, without political pull, to help them overcome whatever handicaps they might have.”[6] In 1909, she founded the National Training School for Women and Girls (NTS) in Washington, D.C. Distinctively, initial funding came entirely from African American supporters.

NTS educated women and girls in a time when formal education for Black females was rare. She was intent on providing her students with strong female role models. She employed an all-woman staff, and all of its teachers were college graduates.[7] The curriculum combined academic courses with Bible classes and practical job-skills training. Burroughs empowered young Black women to gain marketable skills so they could support themselves and contribute to improving “the economic status of African Americans.”[8]

Over time, NTS students came from across the US and Haiti, Puerto Rico, South America, and Africa. Graduates worked as nurses, doctors, administrators, entrepreneurs, milliners, dressmakers, school principals, social workers, and civil servants. Burroughs served as the NTS president for fifty-two years until her death in 1961.[9] Three years later, the Board of Trustees renamed the school “The Nannie Helen Burroughs School, Inc.”[10]

Christian Leader and Mentor

In the nineteenth century, a societal view called the “cult of true womanhood” prescribed separate spheres for men and women: a woman’s rightful place was in the private sphere—the home, while the man’s proper place was in the public sphere—in commerce, politics, and the pulpit. Deeply committed to Jesus Christ, Burroughs believed Christianity empowered her for service in the private and public spheres. She aspired to serve as “foremost a racial evangelist, a beneficiary and vindicator of a religiously grounded race-centered intellectual tradition handed down by black thinkers like John Jasper, Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, Alexander Crummell” and influential Black women such as “Maria Stewart, Jarena Lee, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth.”[11]

Justifying their public work, these women and Burroughs pointed to the examples of men and women in the Bible and biblical passages, like Joel 2:28: “Your sons and daughters will prophesy….” And Burroughs highlighted Christ’s empowerment of women: Jesus, she said, “gave woman a soul…put her feet in the path of service and lifted her head up to show her proud equality with man in mind, heart, and spirit.”[12] Burroughs, who never married, contributed significantly to the Black Baptist women’s movement in the early 1900s “as an important political mentor to the female religious community.” She also acquired “many followers among the male clergy.”[13]

Civil Rights Activist

Women’s right to vote was a national issue in the second decade of the nineteenth century. Burroughs lent her voice to the fight. She argued, “that the ballot would aid women to fight for labor laws designed to protect women and children.” Encouraging women to found suffrage groups in their churches, she reassured them that “practical Christianity included the exercise of the ballot.”[14] Her advocacy united the African American church community with the National Association of Colored Women’s work and the National League of Republican Colored Women.

Through her charismatic speaking engagements and published writings, and as Black newspapers covered her speeches and advocacy work, she gained a nationwide audience. Underscoring the critical need to live a God-centered life, she also addressed “the need to respect black womanhood.” She called out “white women reformers who advocated social purity for white women but ignored the sexual exploitation of black women by white men.” And, she denounced “the sexism of black men.”[15] To explain her perspective on black womanhood, she wrote:

We must have a glorified womanhood that can look any man in the face—white, red, yellow, brown, or black, and tell of the nobility of character within black womanhood. Stop making slaves and servants of our women. We’ve got to stop singing— “Nobody works but father.” The Negro mother is doing it all. The women are carrying the burden.[16]

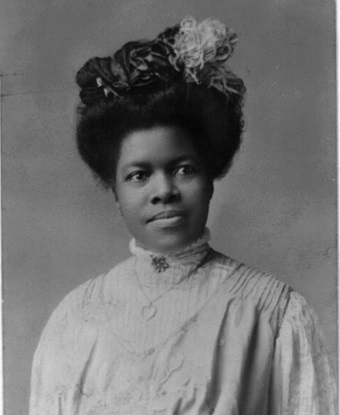

Nannie Helen burroughs

Leading Voice and Role Model

Burroughs connected her faith to her life. This historical woman empowered Black women to live purposeful and productive lives. And through her Christian-based advocacy, she reminded humankind to value their fellow human beings well. A leading Black voice, Nannie Helen Burroughs is a model for us all.

Image: From the National Library of Congress

Read my other posts on historic women of faith here and here. Would you like to learn more about women, the church, and leadership, but are unsure which resources are trustworthy? Download my complimentary Ultimate Resource Guide on Women and Church Leadership here.

[1] “A Religious Portrait of African-Americans,” Pew Research Center on Religion & Public Life, January 30, 2009, 1–22.

[2] Nannie Helen Burroughs with Kelisha B. Graves, ed., Nannie Helen Burroughs: A Documentary Portrait of an Early Civil Rights Pioneer, 1900–1959. African American Intellectual Heritage Series, (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019), 16. https://search-ebscohost-com.dts.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2502108&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

[3] Evelyn Brooks, “Religion, Politics, and Gender: The Leadership of Nannie Helen Burroughs.” The Journal of Religious Thought, Vol. 41, No 2 (1984–85), 7–22. https://web-b-ebscohost-com.dts.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=02a2ce53-a7f9-4ce9-8d00-01f6bfa7ef19%40pdc-v-sessmgr02

[4] Burroughs and Graves, Nannie Helen Burroughs, 15.

[5] Ibid, 16.

[6] Ibid, 16.

[7] Traki L. Taylor, “Womanhood Glorified:” Nannie Helen Burroughs and the National Training School for Women and Girls, Inc., 1909–1961, The Journal of African American History, (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press), Vol. 87, Autumn 2002, 390–402.

[8] Taylor, “Womanhood Glorified,” 395.

[9] Ibid, 398.

[10] Ibid, 400.

[11] Burroughs and Graves, Nannie Helen Burroughs, 17.

[12] Ibid, 18.

[13] Brooks, “Religion, Politics, and Gender,” 9.

[14] Ibid, 20.

[15] Ibid, 21.

[16] Burroughs, “Unload Your Uncle Toms,” Gerda Lerner, ed., Black Women in White America: A Documentary History. (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 550–553 as quoted in Brooks, “Religion, Politics, and Gender,” 21.